AI’s Achilles’ Heel

And Knowledge Creators’ Competitive Advantage

By Ziqian Feng | January 23, 2026

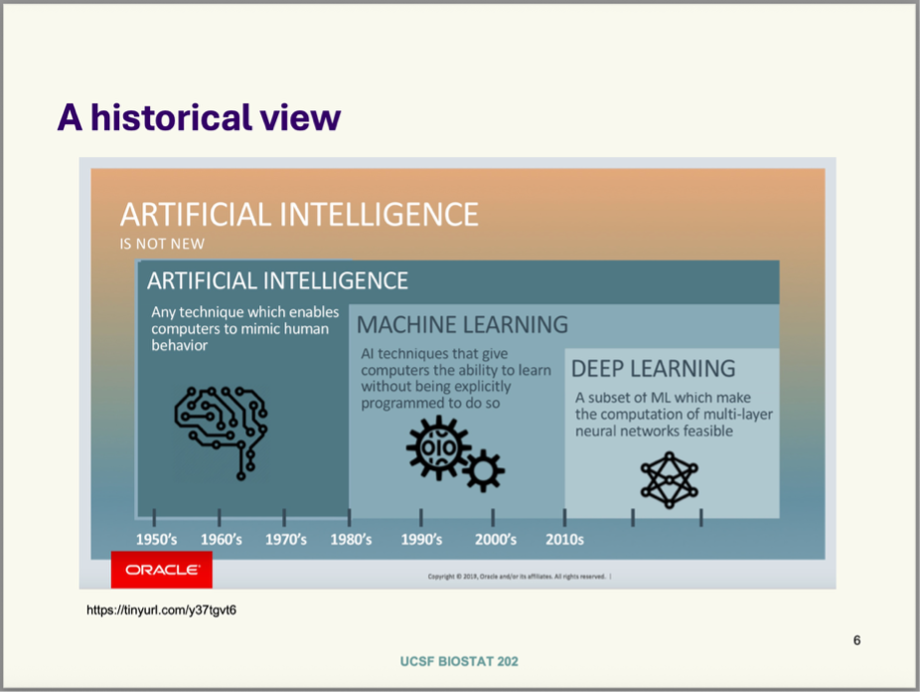

August 2025, San Francisco. There were six screens in the classroom, and all of them read “ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IS NOT NEW.” [1] What a surprise.

It has been several years since the globe became impassioned by AI—impassioned, fearful, hopeful, and overwhelmed. This is not to say that AI has not been helpful in certain realms, but I want to come back to some basics and quiet down any “existential crises in the social science community.” [2] No, AI can never replace social scientists.

In its crudest form, artificial intelligence (AI), defined as “[a]ny technique [that] enables computers to mimic human behavior” has been around since at least the 1950s. [1] Frankly, Blaise Pascal already built a “mechanical calculating machine” in 1642, and after Alan Turing introduced the Turing test (which evaluates a machine’s intelligence) in 1950, we already had an “AI conference” in 1955 (where the name AI was officially coined). [3]

“Machine learning,” in turn, is a subset of AI—“AI techniques that give computers the ability to learn without being explicitly programmed to do so”—and it emerged in the 1980s. [1] “Deep learning,” a further subset of machine learning, “which make[s] the computation of multi-layer neural networks feasible,” became mainstream in the 2010s. [1] And our current magnet “LLMs” (large language models)—think the underlying architecture of ChatGPT (a generative AI)—are a further piece of the deep learning pie. [4]

LLMs are amazing because they can speak “human”—natural languages that are understandable for everyday Janes and Joes, not just expert coders. But I find the adjective “natural” rather artificial here. When we communicate with AI in such natural languages, we are giving commands, not really having a natural human conversation. We are at best wielding a user-friendly tool.

So, what is new? Perhaps the wide availability of ever-advancing LLMs worldwide.

What is advantageous about AI? The speed in dealing with existing, overt information. (Though it also hallucinates and tells lies sometimes!)

What is too much to ask of AI? Anything before the stage of execution.

Prof. Lindquist of that summer biostatistics class always liked to remind us students: “Garbage in, garbage out.” AI can be extremely efficient in processing—maybe even more efficient and careful than the best of human quantitative analysts—but it cannot defy this simple law: garbage-grade inputs in, garbage-grade outputs out. AI has no control over the inputs, in a fundamental sense.

Here also lies a significant difference between data science and social science. Both are interested in the future, a.k.a. the predictive ability. However, the two have very different bottom lines (and incentive infrastructures). Data scientists know neural networks as a processing black box and are not disturbed by this obscurity—as long as a model (using neural networks or not) delivers the highest predictive accuracy, it wins the Kaggle Competition. Meanwhile, social science mandates scholars to first develop a theory before handling the data.

In a way, data science is a “doer,” while social science is a “thinker.” The latter is susceptible to one’s own cognitive and imaginative limitations, while the former’s future success relies on the unchangingness of underlying conditions (for a given model using neural networks to continue to perform well, the underlying assumptions of the neural networks have to remain the same across datasets).

But we know that the only constant is change, and no mortal is omniscient.

Maybe here is the crux. The world is not simply black or white, not a 0 or 1, but a living whole composite of all shades of colors—and sounds and smells and sentiments and aspirations—that morph and reverberate throughout time and space. AI has its unique strengths, but it is awfully limited in the dimensions of data it can receive to process.

It can compute—with or without its black-box neural network thinking, with or without its headache-inducing hallucination. But it cannot feel, it cannot experience the gentle unfolding of human experience and wisdom. It cannot feel the desperation of people in their darkest hours nor the unexpected joy and courage. It can retell the past in its signature binary ways, but it cannot imagine the future with infinite moving parts.

And here is where social scientists come in, with all our imperfect and limited thinking. First of all, we are humans, which means that we are endowed with the ability to perceive ample nonverbal information, including nuanced emotional and spiritual feelings. And secondly, as knowledge creators, we are mandated to think outside the box and formulate theses that are yet nonexistent on the web, therefore unbeknownst to any generative AI.

How do we do this, especially at a policy school? Maybe when the world is focused on upgrading its arsenals with the latest AI development, we also examine the impact of AI on our children, the true defenders of our future. Maybe when companies boast about their cost-saving and productivity-boosting with AI adoption, we also look at the human cost—for after all, many wealthy communities are silently enduring a loneliness epidemic [5] that goes beyond numbers and accounting.

AI’s Achilles’ heel lies in its honest limitation. It was never made to be the master of human fate. It was created as an imitation. It may replace us in non-emotional processing, but it will never have a real human texture and warmth. It lacks direction, and it does not have access to inspiration.

Knowledge creators’ competitive advantage thereon lies in clear-eyed direction-giving and question-posing. Both humans and AI are currently inundated by data, but only humans can formulate meaningful questions that reveal societal heartaches and propel humanity forward.

Reference

[1] Karla Lindquist. “BIOSTAT 202: Opportunities and Challenges of Complex Biomedical Data: Introduction to the Science of ‘Big Data’ - LECTURE 4: Introduction to Machine Learning & Supervised Learning (Regression).” Summer 2024. San Francisco. Microsoft PowerPoint presentation. Slide 6 – using a graph produced by Oracle (*On 12 Jan. 2026, at the time this opinion piece was written, the authorcould not access the original Oracle source that first published the graph).

[2] John Burn-Murdoch and Sarah O’Connor. “The AI Shift: Agentic AI is coming for quantitative research.” Financial Times, 8 Jan. 2026. https://www.ft.com/content/91836acb-ab0c-4680-9dcf-c4de9e9917c5.

[3] “History of Artificial Intelligence.” The University of Queensland, https://qbi.uq.edu.au/brain/intelligent-machines/history-artificial-intelligence. Accessed 12 Jan. 2026.

[4] Cole Stryker. “What are large language models (LLMs)?” IBM, https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/large-language-models. Accessed 12 Jan. 2026.

[5] Office of the U.S. Surgeon General. Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community. 2023, p. 4. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-social-connection-advisory.pdf.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Ziqian Feng is an interdisciplinary scholar pursuing a PhD in Public Policy at the Schar School of Policy and Government. Her current research focuses on global demographic trends and opportunities for strategic partnerships.